RBAC Isn’t Dead: Meet ReBAC

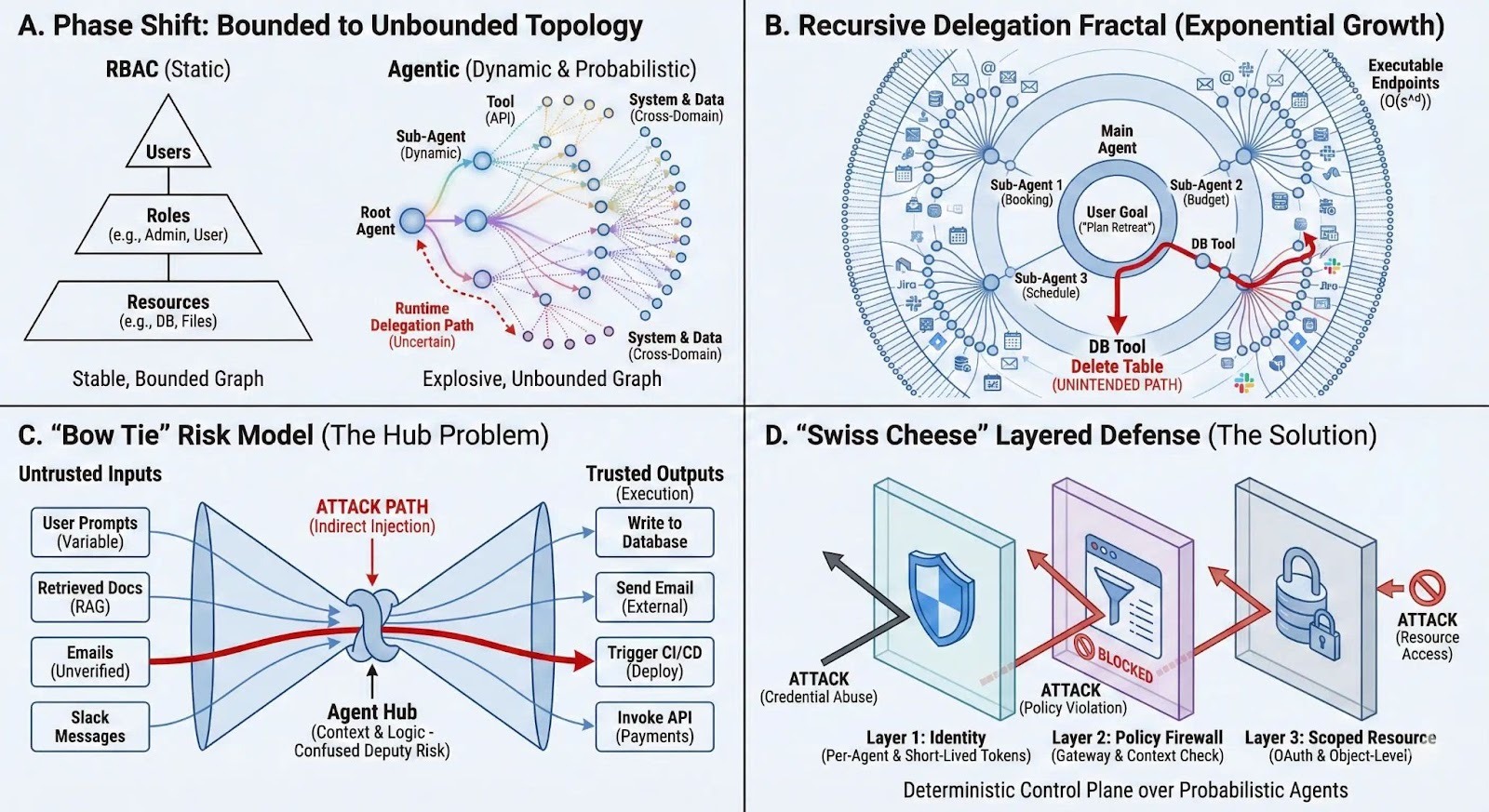

Enterprise IAM was built for a simpler shape of work: people log into a handful of apps, roles map cleanly to job functions, and permissions change slowly. In that world, RBAC (Role-Based Access Control) scales.

Most organizations today don’t live in that world anymore—even if they don’t have “autonomous agents.”

What they do have is this:

- Users authorizing OAuth access between SaaS products (Slack, Notion, GitHub, Google Workspace, ticketing systems, CRMs).

- “Smart” features and copilots inside each product that can read, summarize, suggest, and sometimes act.

- Automations and integrations that quietly move data across systems once you’ve granted them permission.

So the real access model increasingly looks like:

People authorize apps → apps act on their behalf → actions touch specific objects (docs, repos, channels, tickets) → those objects live inside shared workspaces with shifting relationships.

That’s why IAM is becoming less about “who has what role” and more about “who is related to what object, in what workspace, through what kind of sharing.”

You can call that ReBAC (Relationship-Based Access Control). But the important point for most companies is simpler:

You don’t need a new, centralized “agent platform” to benefit from relationship-based thinking. You need to govern OAuth, and you need object-level guardrails inside the tools you already run.

What changed (even without “real agents”)

In most orgs, “agents” are not a separate workforce of autonomous bots. They’re:

- a Slack app that posts and reads messages,

- a Notion integration that can read pages and update databases,

- a GitHub app or token that can open PRs, read code, create issues,

- a Google Workspace connection that can access Drive, Gmail, and Calendar,

- an AI assistant inside those products that can operate across what it can see.

Once OAuth is granted, these tools can behave like a personalized delegate: fast, persistent, and able to chain actions across systems.

This creates two practical realities:

- Authority is increasingly exercised by software acting “as you,” not only by you.

- The true security boundary is often the object (this doc, this repo, this channel), not the app.

Where RBAC breaks down in connected SaaS

RBAC still helps with coarse decisions:

- who can access GitHub at all,

- who can use Google Workspace,

- who can install Slack apps,

- who can be an org admin.

But RBAC strains in the places where modern SaaS work actually happens:

1) The important decisions are object-level

Most incidents and “oops” moments aren’t “someone accessed GitHub.” They’re:

- someone shared a sensitive Drive folder externally,

- a token pushed to the wrong repo,

- an integration read a private Notion space,

- a workflow posted data into the wrong Slack channel.

RBAC answers: “Can you use Drive?” Security needs: “Can you share this folder outside the company?”

2) SaaS permissions are relationship-driven, not role-driven

Access is usually justified by relationships:

- membership in a workspace/team,

- ownership of a project,

- being assigned to a ticket,

- being in a repo team,

- having a doc shared with you.

RBAC can approximate this, but it tends to produce either:

- role explosion (“Repo-Write-Project-A”, “Repo-Write-Project-B”…), or

- over-broad access (“just make it admin so the integration works”).

3) OAuth turns “permission bundles” into durable blast radius

OAuth grants often look like “allow this app to read files” or “access Slack workspace.” Those scopes are frequently broader than people realize, and they persist until revoked.

That’s not a theoretical problem. It’s a day-to-day operational one:

- new apps get authorized during experimentation,

- the app becomes “sticky,”

- nobody remembers it exists,

- and it keeps its access long after the original need is gone.

4) Input manipulation replaces credential theft as a common path

You don’t always need to “hack” an account if you can steer what a delegated tool does:

- a doc someone reads contains instructions the user (or assistant) follows,

- an issue template nudges an automated workflow,

- a page, email, or ticket text shapes what gets summarized or copied.

Even without full automation, steering a legitimate, authorized action is a recurring failure mode in connected workflows.

ReBAC, translated for normal companies

ReBAC can sound like “build a graph database and evaluate relationship paths.” Most orgs won’t do that.

Here’s the practical version that is achievable:

Relationship-based control already exists in your tools—use it deliberately

Your SaaS stack already runs on relationships:

- GitHub: org → team → repo → branch/PR

- Google Drive: domain → shared drive → folder → file → sharing settings

- Slack: workspace → channel → membership → app install permissions

- Notion: workspace → teamspace → page/database → share permissions

The strategy is to standardize how you use those relationship controls, and to treat OAuth connections as privileged.

Think of it as:

- RBAC for “entering the building” (access to the tool, admin vs user)

- relationship/object controls for “what you can touch inside” (which repos/docs/channels, what actions, and what sharing boundaries)

No new grand architecture required to start—just consistent policy patterns, enforced in the systems people actually use.

What to do that’s realistic for most organizations

1) Treat OAuth authorization like granting a new employee access

Most companies are looser with “Authorize app” than they would ever be with adding a new admin.

Minimum viable controls:

- Maintain an inventory of OAuth apps and integrations (first- and third-party).

- Require admin approval for high-risk scopes (or for any third-party app).

- Prefer least-privileged scopes and avoid “full workspace / all files” grants when narrower options exist.

- Periodically review and remove unused apps/tokens.

If you do only one thing: alert on new OAuth grants and new app installs. That alone catches a lot.

2) Put guardrails on the highest-risk actions, not on everything

You don’t need perfect least privilege everywhere. Start with actions that create outsized blast radius:

- external sharing / public links

- exports / bulk downloads

- permission changes (adding collaborators, granting org access)

- writing to production branches / triggering deploys

- creating API keys / tokens / new integrations

Make these actions require either:

- a stronger condition (admin-only, allowlist-only),

- a second step (approval / confirmation),

- or at least a high-signal audit trail and alerting.

3) Standardize “object boundaries” inside each core tool

This is where relationship-based thinking pays off without fancy infrastructure.

Examples of practical boundary patterns:

- Google Drive / Notion: default to teamspaces/shared drives with controlled sharing; restrict external sharing by default; allow exceptions via process.

- GitHub: use teams mapped to repos; enforce branch protections; require reviews for sensitive repos; use CODEOWNERS where appropriate.

- Slack: tighten who can install apps; restrict which apps can access message content; use private channels deliberately for sensitive workflows.

The point is consistency: “where sensitive work lives” should be structurally separated from “where experimentation happens,” so relationships enforce boundaries naturally.

4) Limit “copilot connectors” and AI features to approved data zones

AI assistants become risky when they can read broadly and write freely across systems.

Practical controls most orgs can apply today:

- Allow AI access to specific spaces/drives/repos rather than everything.

- Prefer configurations where AI can suggest but not execute high-impact changes.

- Avoid connecting AI tools to the most sensitive stores until you have confidence in logging and boundaries.

- Make “what data can be indexed / retrieved” an explicit governance choice, not a default.

Even if the assistant is “just summarizing,” summaries can move sensitive data into less-controlled places (like chat). Boundaries still matter.

5) Centralize logs enough to investigate quickly

Most organizations don’t need perfect lineage graphs. They need to be able to answer:

- Which integration did this?

- Acting for which user?

- On which object?

- With what scope?

- When was access granted?

Centralize audit signals where you can, and at minimum monitor:

- new OAuth grants/app installs,

- permission changes,

- external sharing events,

- unusual bulk access.

A pragmatic adoption path (low drama, high impact)

- Pick one domain where RBAC is obviously too coarse Docs (Drive/Notion), code (GitHub), or chat (Slack) are common.

- Define the 5–10 actions you never want to happen silently External share, export, permission grant, prod write, etc.

- Enforce boundaries using the tool’s native relationship model Teamspaces/shared drives, repo/team mappings, channel/app install controls.

- Tighten OAuth around that domain Require approval for high-risk scopes and block unknown apps.

- Iterate with real usage Don’t chase theoretical perfection; reduce the most common and highest-impact failure modes.

Bottom line

You don’t need a future where autonomous agents run everything for this to be true:

Connected SaaS already behaves like delegated automation. OAuth turns those connections into durable authority. And the real security decisions are increasingly object-level and relationship-driven.

So the practical evolution isn’t “replace RBAC with a graph database.” It’s:

- keep RBAC for tool entry and admin boundaries,

- add relationship/object guardrails inside each core platform,

- and govern OAuth + integrations like the privileged access layer it has become.

That combination is achievable for typical organizations—and it maps to how work is actually done in Slack/Notion/GitHub/Google Workspace style environments.