Identity Architecture for the Modern SaaS Stack

1. Executive Summary: The Identity Decision Has Changed

For many years, workforce identity architecture was straightforward. A company maintained a single directory, connected it to a single identity provider (IDP), and integrated most critical applications using SAML (authentication) and SCIM (provisioning). Authentication, provisioning, and access control were largely centralized.

That model no longer reflects reality.

Modern companies operate across multiple identity surfaces. Employees authenticate using different protocols depending on the application. Teams adopt tools independently. Applications manage their own internal permissions. AI systems and integrations exchange credentials without human involvement. As a result, identity is no longer a single control plane—it is a distributed system.

This creates a common point of confusion: organizations believe that selecting the “right” IDP will restore central control. In practice, no single IDP can govern the entire environment. The architectural decision is not which vendor to use, but how to design for consistency across heterogeneous identity systems.

The core question for leadership is no longer:

“Which IDP should we standardize on?”

It is:

“Where do authentication, authorization, lifecycle automation, and governance each belong—and how do they work together?”

2. Identity Surfaces in a Modern Environment

Modern identity architectures consist of several distinct but overlapping surfaces, each optimized for a different purpose.

Enterprise IDPs (e.g. Ping, Okta, JumpCloud)

Enterprise IDPs are designed primarily as authentication control planes. They excel at enforcing login security through MFA, conditional access, device posture, and centralized credential management.

They integrate with applications primarily via:

- SAML

- OIDC

- SCIM (where supported)

When applications fully support these standards, enterprise IDPs provide strong and reliable control. However, their scope is inherently limited to the applications that implement these protocols correctly and completely.

Enterprise-Social IDPs (Microsoft and Google)

Microsoft Entra ID and Google Workspace Identity serve as both directories and OAuth/OIDC providers. In practice, they function as enterprise-social IDPs.

Modern SaaS vendors prioritize these platforms because OAuth:

- Is faster and easier to implement than SAML

- Works equally well for users, services, and integrations

- Aligns with API-first and AI-enabled products

As a result, many new applications support “Sign in with Microsoft” or “Sign in with Google” as a default, sometimes long before they support SAML or SCIM.

Application-Native Identity and Authorization

Every application maintains its own internal authorization model:

- Roles (Admin, Editor, Viewer, etc.)

- Permissions and scopes

- Teams, workspaces, or org structures

This layer determines what users can actually do. It is also the least standardized and the least visible from centralized identity systems.

The Implication

Identity today is not one system. It is a mesh of authentication and authorization layers, each with different capabilities and constraints. Any architecture that assumes a single plane of control will have blind spots.

3. Authentication vs Authorization: The Core Distinction

A key architectural mistake is conflating authentication and authorization.

Authentication answers the question:

“Who are you, and how do you prove it?”

Authorization answers the question:

“What are you allowed to do once inside the system?”

Enterprise IDPs are optimized for authentication. They ensure that users log in securely. They are not systems of record for permissions, roles, or entitlements across applications.

Even when SAML is used:

- Roles are often assigned inside the application

- Permissions evolve independently over time

- OAuth tokens and API keys bypass SSO entirely

This means that centralizing login does not centralize access control. Authorization state remains fragmented across applications, regardless of how consistent authentication appears.

4. Architectural Options and Their Tradeoffs

Option 1: SAML-First Enterprise IDP Architecture

In this model, the organization attempts to route all applications through a SAML-centric enterprise IDP.

Advantages

- Strong, centralized authentication controls

- Familiar governance model for IT and security teams

- Clear login enforcement

Limitations

- Many modern applications are OAuth-first and SAML-later (or never)

- SCIM support is inconsistent and often incomplete

- Authorization still lives inside applications

- Tool adoption slows as teams wait for SAML enablement

This approach often creates a false sense of coverage: authentication is controlled, but authorization visibility remains limited.

Option 2: OAuth-First Enterprise-Social Architecture

Here, applications authenticate directly through Microsoft or Google using OAuth/OIDC.

Advantages

- Low friction for users and teams

- Broad compatibility with modern SaaS

- Faster adoption of new tools

Limitations

- Lifecycle events (onboarding/offboarding) are decentralized

- Shadow onboarding increases

- Access governance becomes reactive rather than policy-driven

Without additional controls, this model trades speed for reduced visibility.

Option 3: Hybrid Architecture (The Common Reality)

Most organizations operate a hybrid model:

- Enterprise IDP for some SAML-based apps

- Microsoft or Google OAuth for many others

- Application-native permissions everywhere

This reflects reality, but it introduces fragmentation:

- Policies are inconsistently enforced

- Offboarding is error-prone

- Audit evidence is scattered

Hybrid architectures require explicit design choices to manage complexity.

5. The SSO and SCIM Tax

Attempting to force consistency by standardizing on SAML and SCIM introduces a significant cost, often referred to as the SSO tax.

This tax includes:

- Paying for enterprise SaaS tiers solely to unlock SAML or SCIM

- Purchasing IDP governance add-ons

- Engineering time to integrate and maintain connectors

- Operational overhead to manage partial implementations

Even after paying this cost:

- Coverage remains incomplete

- OAuth-based apps and integrations remain outside the model

- Internal permissions are still not fully visible

From a CTO perspective, the SSO tax is not just financial—it affects velocity, flexibility, and architectural clarity.

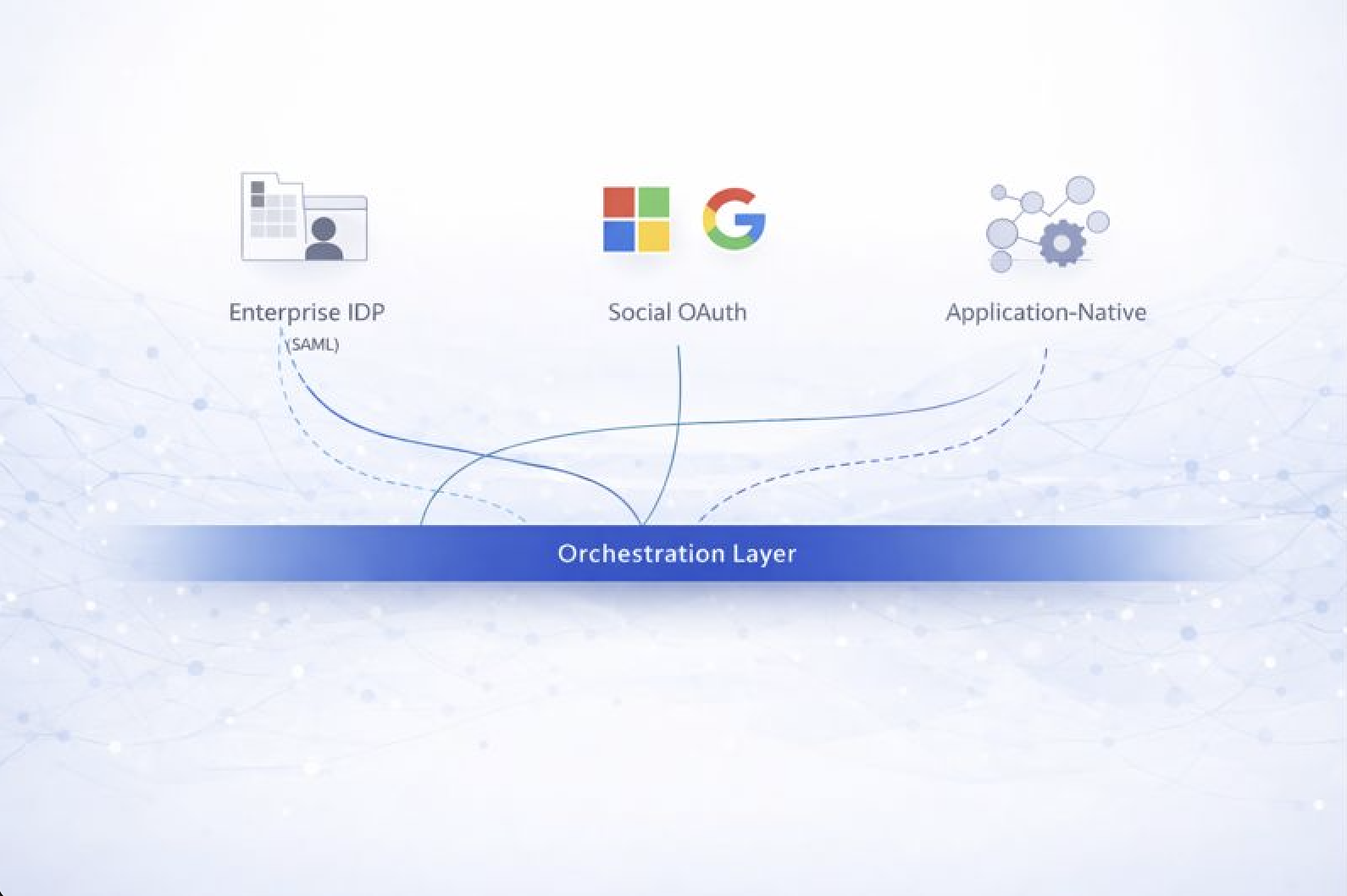

6. The Emerging Identity Architecture Pattern

Modern organizations increasingly separate identity responsibilities across layers:

Authentication Control Plane

- Enterprise IDPs (Okta, JumpCloud, Entra)

- Focused on secure login and access conditions

Enterprise-Social OAuth

- Microsoft and Google as primary adoption paths for SaaS

- Optimized for velocity and compatibility

Applications

- The true source of authorization state

Orchestration and Governance Layer

- Normalizes identities across systems

- Automates lifecycle events across auth types

- Enforces policy consistently

- Provides audit-grade visibility

This layered approach acknowledges that fragmentation is structural, not accidental.

Conclusion

The modern identity challenge is not choosing the right IDP. It is designing an architecture that accepts multiple identity surfaces while maintaining consistency, security, and operational control.

Organizations that succeed do not eliminate fragmentation—they manage it deliberately. They separate authentication from authorization, avoid paying unnecessary SSO tax, and invest in orchestration where centralization is no longer possible.

This is the identity architecture reality modern CTOs must design for.